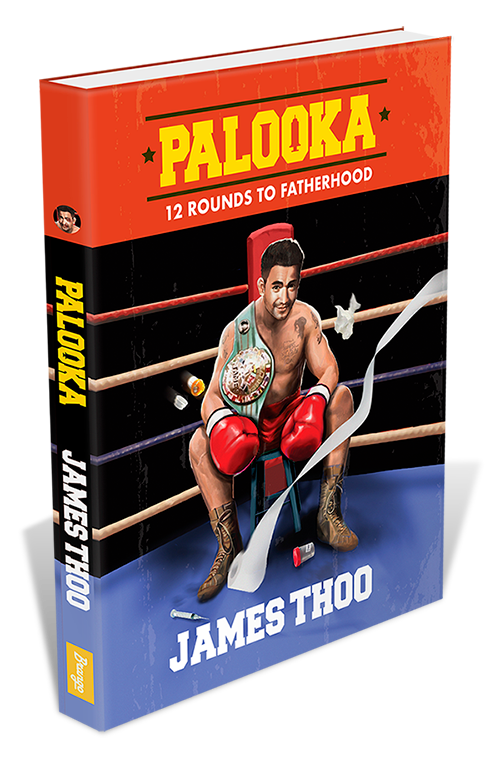

palooka: 12 Rounds To Fatherhood

You gotta fight

For your right

To daddy

palooka: 12 Rounds To Fatherhood

You gotta fight

For your right

To daddy

Available in Stores

Available in Stores

Why it is more important than ever to talk about Fatherhood — and yet so. Damned. Hard

I’ve met a lot of people over the past few years who have confided in me their struggles with infertility. The surprising ones were all men. Not because I was surprised to find that they were infertile, but because I didn’t really even know them.

Why it is more important than ever to talk about Fatherhood — and yet so. Damned. Hard

I’ve met a lot of people over the past few years who have confided in me their struggles with infertility. The surprising ones were all men. Not because I was surprised to find that they were infertile, but because I didn’t really even know them.

“A book of confronting self-doubts, male identity and infertility”

What folks like you and me are saying

Unpretentious and irreverent—the closest you will come to seeing someone fighting for fatherhood tooth and nail and telling it as it is.

Santosh SN

It’s been years since I’d read a book from start to finish...and I’m so glad Palooka changed that. This story subverts our expectations of what it really means to be a man in a world where masculinity is synonymous with virility.

MARY TAY

Funny. Vulnerable. Warm like cigars and cold beer with a best friend.

Jedidiah Huang

What You REALLY Need to Think About if You Want to Have Kids

HERE’S WHAT YOU GET:

HERE’S WHAT YOU GET:

the fight for fatherhood

Screenwriter James Thoo’s memoir dissects in vitro fertilisation (IVF) — “one prolonged uppercut to the scrotum” — revealing its silent blows to the male psyche.

He confronts toxic masculinity, his estrangement from his father, and the near-death of his wife, through rounds of bad news, medical ambiguities, and self-doubt about the quality of his ejaculate. He finds himself returning to his role models: history’s legendary boxers who never quit, and fought to win.

This book is must-have armour for men and women going through assisted reproduction treatments, IVF doctors who need to mentally prepare patients, and anyone yearning to be a parent.

MEET THE AUTHOR

James Thoo is an award-winning screenwriter, author and playwright, whose career in the arts has occupied the better part of the past 15 years — apart from his stint as a professional boxer when he was 27. He was editor of the industry-leading film website, Joblo.com, and has been published in global media channels including The Huffington Post and the New York Times.

After he transitioned to screenwriting, he worked on several features including The Rude Mechanical (2006), which he wrote for Ravenwood films in Los Angeles, the award-winning Malaysian film, Jarum Halus (2008). Sonata, which in 2015 placed number one on Scriptshadow’s annual list of the best unproduced screenplays in Hollywood, and his boxing feature, Hurt, is currently in pre-production in Colorado with Bruise productions.

His contribution to Singapore’s arts scene began when he settled here with his Singaporean wife, Alicia in 2017. That year he wrote the play Stool Pigeon, the maiden production for Thomas Pang’s theatre company, Room to Breathe. His most recent play, The Jugular Vein, was produced and staged by The Haque Collective to sell-out audiences in 2019.

Between writing and caring for his family, he enjoys great pancakes, rap music, Jordan 1s, combat sports and, of course, movies. If he had to be a character in a movie, it would be Doc Holliday in Tombstone.

Since then, he has coached aspiring writers in conceptualising and creating original works at the Haque Centre of Acting and Creativity, in addition to undertaking independent film projects.

Conversations with James:

After I got my initial diagnosis. Although it wasn’t a book then. It was, I thought, just an essay of some kind. I guess it became a book when I realised this wasn’t going to be the two or three month instant-baby procedure I had assumed it was, and the content kept piling up, and so did the essays.

I think, just how utterly minor the male role was. It’s very humbling. The woman’s body has to hit this delicate and precise balance, and to get there she has to undergo hundreds of checks and scans, and she has to diet and suffer through medication and injections, the mood swings and the weight gain that come with all of those, time off work, incredible physical discomfort. For the man, all you have to do is ejaculate into a tub. And even that I couldn’t do successfully. So, it’s a very, very humbling thing.

I played a lot of video games. And wrote this book. Between those things and all the self-loathing I was doing, there really wasn’t much time for anything else.

I mean, the nature of this question is already kind of gross for me because I’m a relatively healthy, certainly happy man on the kinder side of forty who thoroughly enjoys his life. I think I’m one of the last people to be talking about what’s challenging for men. But I guess I would hazard a guess at the indoctrinated expectation placed upon men to provide? Or that they place on themselves to provide? Because I think about aspiring artists and athletes, who feel forced to abandon their dreams on account of they need to start providing for a family immediately and there’s no time to really cultivate their craft and see how good they could have been. And especially with young athletes. I guess, at a push, a writer can learn in his spare time and go back. Mark Twain was forty one when his first novel was published. Sophocles took eighteen years to write Oedipus Rex. Would-be athletes have no such luxury. Most careers last less than eighteen years. Sergio Martinez and Deontay Wilder are probably the only examples of boxers who committed to the sport late and still enjoyed real success, that I can think of. I know that in the grand scheme of things there are more difficult things that young men are facing in the world today, but for some reason wasted potential is something that really makes me sad.

My wife likes to tell this story of me breaking my hand and then happily playing goalkeeper the next night at my five-a-side football game and using my hand to block shots that were being blasted in my direction for an hour. She tells it to demonstrate how stupid and irresponsible with masculinity I am, and at every dinner party she tells it, it always has the desired result because being irresponsible with your body in the name of masculinity is rightfully idiotic. But that was the narrative I grew up with. Pain is temporary and pride is permanent. Don’t be a bitch. Bruises heal. All of that stuff. If she told my brother that story, the response would have been significantly different. We were raised by the same man. But it doesn’t work at all today because people understand that it isn’t cool or manly to hurt yourself. I’m slowly getting it. I even go to the doctor sometimes now.

Probably how little people are expected to talk and be open about their emotions. And look, I don’t think I’m there yet either. In fact, if anything I belong more to my father’s generation than I do my own, probably because he was such a titanic influence in my development. It might seem like I’m part of this new woke generation because I wrote this book but that’s the rub - I wrote about it. I never spoke to my father about any of the things before that. But I’m trying. After he read the book, he and my brother and I sat down and had a cigar and a few bottles of whiskey together and had probably the best conversation any of us have ever had.

He read a draft and didn’t say much. And then a few days later, he completely out of nowhere asked me if I thought he had been too hard on me when I was growing up. Which, I definitely didn’t feel was the case, and I told him so. He didn’t really say anything else after that, so I guess reading the book didn’t really change his opinion of his role in my young life at all.

I think it’s a tough question because it makes some supposition that ‘boxers’ have this homogenous set of shared urges or desires or whatever. I was always a guy who worships at the altar of defensive craft, so every time I got in the ring I never thought I was gonna get beaten up. I don’t think there’s any correlation to be drawn from boxing to my dad, or the kids on our estate beating the dog shit out of me with semi-regularity. But, I mean, contrast that to someone like Jake LaMotta or Mickey Ward, those real, world class tough guys and maybe there’s something there. Maybe, because so many great boxers were birthed into abject poverty, they see boxing as a way to level the playing field. All they have to do is be more willing to get beaten up than the other guy. And so they’re happy to get the shit kicked out of them to spite their face. But that mindset is as alien to me as that of people who sign up to work in an office for 80 hours a week.

I mean, the first thing that you realise if you spend any time at all around a boxing gym is that there’s always gonna be someone out there who can kick your ass. Those people that don’t like the constant physical reminder of that fact necessarily phase themselves out of the boxing experience, and those that see the reminder as an opportunity for compelling competition or for personal growth stick around. Then you multiply that by the ten, fifteen years it takes for that person to get a foot in the professional game, and it’s pretty easy to see why only the resilient among them make it.

So much of the mentality that goes into boxing is the self-belief that victory can be achieved, on some level, through nothing but sheer force of will. That’s how you get things like Chavez-Taylor and Marciano-Walcott, but also how you explain any time that anyone ever challenged Sugar Ray Robinson to a fight. I mean, he was probably the most naturally skilled boxer of all time, and he was also taller, bigger, faster, stronger, hit harder, and had a longer reach than Jake LaMotta, and LaMotta still challenged him six times. It sounds like madness. I guess it was. But in spite of it all, LaMotta did beat him once. So what does that say about all those tangible attributes, and how much does it say about the power of force of will? Force of will becomes that safe haven, that a fighter knows he can retreat to when it looks like everything else has failed.

Unfortunately, that’s just not the case when it comes to the process of IVF. In fact, essentially none of it can be achieved through sheer force of will. So little of the outcome is in your hands. It becomes a trust exercise. And I guess the specific paradox with boxing is that in boxing, the more punishment you’re willing to endure, the better your chance is of winning. With IVF, again, the opposite is true. You need to take care of yourself. Mentally and physically, to give yourself the best chance of success. This can be really difficult to reconcile.

This is going to be a tough one because my favourite boxer was Carlos Monzon, which is kind of like saying your favourite director is Roman Polanski, or Ted Bundy is your favourite legal professional. It just so happened that I didn’t find out anything about Monzon’s life outside of the ring until so many years after I watched him box. And so I guess, with all of his atrocities in mind, I would ask him if he regretted the way that he lived his life. As evil and sociopathic as he seemed to be, I suspect his answer would be no, and that he died a happy man. Which, if there’s a greater indictment of boxing and the nature of celebrity in the society that we live in than that, I certainly can’t think of it.

What’s interesting (or extremely fucked up) is, I thought about whether I should not say I was a Monzon fan, and choose another. In which case, my answer would have been Stanley Ketchel. After becoming middleweight champion of the world and then died at the age of twenty four. And I think I would have asked him the same question. And I suspect his answer would have been the same, too. So, go figure.

There was never a moment that I considered this but there were times that I tried to make myself comfortable with the notion of adopting, just in case IVF happen for us. It wasn’t a difficult notion to accept, though, honestly, because we were only this position because of my genetics, and so maybe recreating more of me wasn’t the best idea in the world anyway.

Alicia was never anything but supportive of my writing about our experience, no matter how personal it got. She’s the best.

My mom was also the best. She and Alicia and Kenneth from 30 Rock would’ve been dead-heat gold medalists and the all-time bestness Olympics. She would’ve said the book was so good that it shouldn’t just win a Pulitzer, but that they should recall all the other Pulitzers they gave out before and melt them all down to make one big super Pulitzer for me. Except maybe Annie Proulx’. My mom loved The Shipping News.

That infertility affects people all over the world, from all backgrounds, no matter how well you eat, or how often you go to the gym. And that as a result, there’s nothing shameful about it. That you really shouldn’t be ashamed to talk to someone about it if you want to. And that in turn if someone tries to talk to you about it, then, you know, don’t be a dick.

Because it’s fucking embarrassing. And I don’t think that’s a strictly masculine phenomenon either. I’ve never seen it happen in person but two decades of television and movies seem to suggest strongly that one woman calling another woman ‘barren’ has always been a pretty solid way to get wheel kicked in the vagina. So, yeah. I think it sucks equally for both genders. Although I presume that women’s friends are less likely to call you a pussy. At least derogatorily anyway.

The surprising reaction that I got was overwhelming support. I always wanted to be a modern day Steinbeck, and so that characters I tend to write are never the most endearing, and the misadventures that they get up to are never the most charming. I mean, in this case the character is a self-loathing man-child, and in the first chapter his misadventure is the odyssey of ejaculating into a tub, so it’s not like I’m all of a sudden writing Edith Wharton or something. But the support has been surprising.

Look, I can’t speak for other people. I was there at every single doctor’s check-up, which, I mean, there are a lot of. Some weeks it’s every day. One after another, for years. And I didn’t miss one. But I know there are husbands who don’t go to any. And again, I can’t speak for why that is, or how it affects them, but in my experience, it took a significant mental toll. And I’m not saying necessarily that I needed someone to talk to, or that I was getting depressed or anything like that, just that the question of whether or not I was ever going to be a father became literally all that I thought about. Literally. For years. And the first thing that does is get really tiring, really fast. And the second thing is that it turns everything into a trigger. People flippantly mentioning when they will have kids, people neglecting the kids they have. People having more kids when I couldn’t have one. Everything pissed me off. And I mean, I guess my friends and my wife’s friends will have to be the ones to tell you how I managed that - I’d like to think I did pretty well at hiding my mood. But it made almost all social events pretty unbearable. Everything made me either incredibly angry, or incredibly sad and jealous.

I would’ve chilled out, I guess. That spectre of being a childless man hung ominously over me like the sword of fucking Damocles for years, and the older I got the more affecting it was. The stress incurred over this period probably shortened my life by at least a decade.

"A must-read book to determine if a financial and emotional commitment to an IVF ‘Maybe Baby’ is right for you."